DISCLAIMER: this case study will likely look incredibly odd to you. This is a non-visual design project, and therefore visualisation is not key, but iteration and user feedback are. If you have the time, use it to understand how we can design to be more inclusive, accessible and less visual centric!

Context

Bidding for and receiving funding from Epic Games via their MegaGrant program as well as Lancaster University’s research grant for participatory research to develop an audio only game. Co-designed in collaboration with sight loss charities and visually impaired people through workshops and gameplay testing in an iterative design process.

Initial Interviews

Through initial (anonymous) interviews and discussions (conducted after ethics approval) with 20 blind and visually impaired people who have played games in the past or have interest in playing games going forward, pain points which existed for them were:

Interviewee 1

“Audio only games can tend to be really easy compared to other games.”

“Visual games rely on me having some sight, which not all blind people have.”

Interviewee 2

“All the audio games that I’ve tried before seemed to be very much like books, in the sense that they felt like they were all about stories and not much about play like tetris or pacman. I guess I just want to play games not listen to them, and if possible with other people.”

Interviewee 3

“I don’t bother trying games much anymore as games consoles are so expensive just for the sake of playing 1 or 2 games which are accessible to me.”

“I would like to play games more, but I want to get away from using my phone for everything. I like the idea of computer or controller games where I can just plug and play for a short period..”

Pain Points

After these initial interviews and discussions including some of the above comments, several starting pain points became clear:

1. Audio only games are usually overly easy.

2. Visual games rely on sight to be playable at any level.

3. Audio games that do exist aren’t gameplay centric.

4. Games require expensive hardware which isn’t worthwhile when most titles for that hardware aren’t accessible.

5. Blind gamers want changes to break away from their phone and touchscreen.

6. Blind gamers don’t just want a specific type of game, but access to more games in general to feel included.

What we will design?

To address these pain points, we will develop a gameplay centric (3), increasing difficulty (1) audio only game without any visual elements (2). This will explore mainstream desktop hardware through both Mac and Windows (4, 5). This game will be a maze exploration game where players avoid enemies and reach endpoints due to navigation and spatial awareness being focal, with many of the learnings about navigation being transferable to wider games including multiplayer ones (6).

Why are we doing this?

Blind and visually impaired people are marginalised in the space of games and spatial UX due to the focus these designs spaces have on visuals (6). Audio comes secondary and games are usually designed to function without audio. When audio games do exist, they usually are narrative focused and not overly challenging (1). Not only can this audio game provide challenging gameplay, but it can also position itself as an example of how non-visual accessibility can be implemented into more mainstream games and virtual spaces which aren’t screen reader adaptable due to their non-linear user experiences (6). Accessibility features also have a track record of being useful for everyone with less than 20% of people turning subtitles off in recent Ubisoft titles when they are enabled by default!

User Persona

Chris H. is 25 years old. He lost his sight at 14 and has found it hard to connect with friends as they have gotten more into online games since the global pandemic (2). He is hard working, intelligent and thoughtful, but desires to connect more with his peers through things they love. He can’t access the games his friends do due to their reliance on visual elements, and he doesn’t want to buy the newest hardware without being able to benefit from the fancy visual graphics. He used to love competing against his friends in games like tetris and mario kart but can’t anymore (1, 3).

This game is also aimed to provide intrigue to existing gamers, developers and designers to bring awareness to the issues around visual centric game design (6).

Constraints

The game needs to be buildable within mainstream engines and hardware (4) as a proof of concept for accessibility features. Headphones and speakers are possibilities, as well as keyboard and mouse or controllers to reduce upfront costs for players (4). The game can have no visual elements (2) and needs to pose increasing challenge to maintain flow state between chaos and order for players (1). The game should be self explanatory within its own onboarding without existing game knowledge requirements.

Assumptions

(i) Audio game onboarding should be paced similarly to visual game design.

(ii) All sounds should be spatialised to improve information richness.

(iii) Control schemes are likely to be different from visual games.

(iv) Audio games need to be simplified further than visual games.

Design Phase 1

After situating the design of the game, we tried various engines, from Unity to Godot, eventually settling on Unreal Engine due to its built in spatial audio capabilities. through development and testing we found a major pain point of control schemes which became integral to the continued design process.

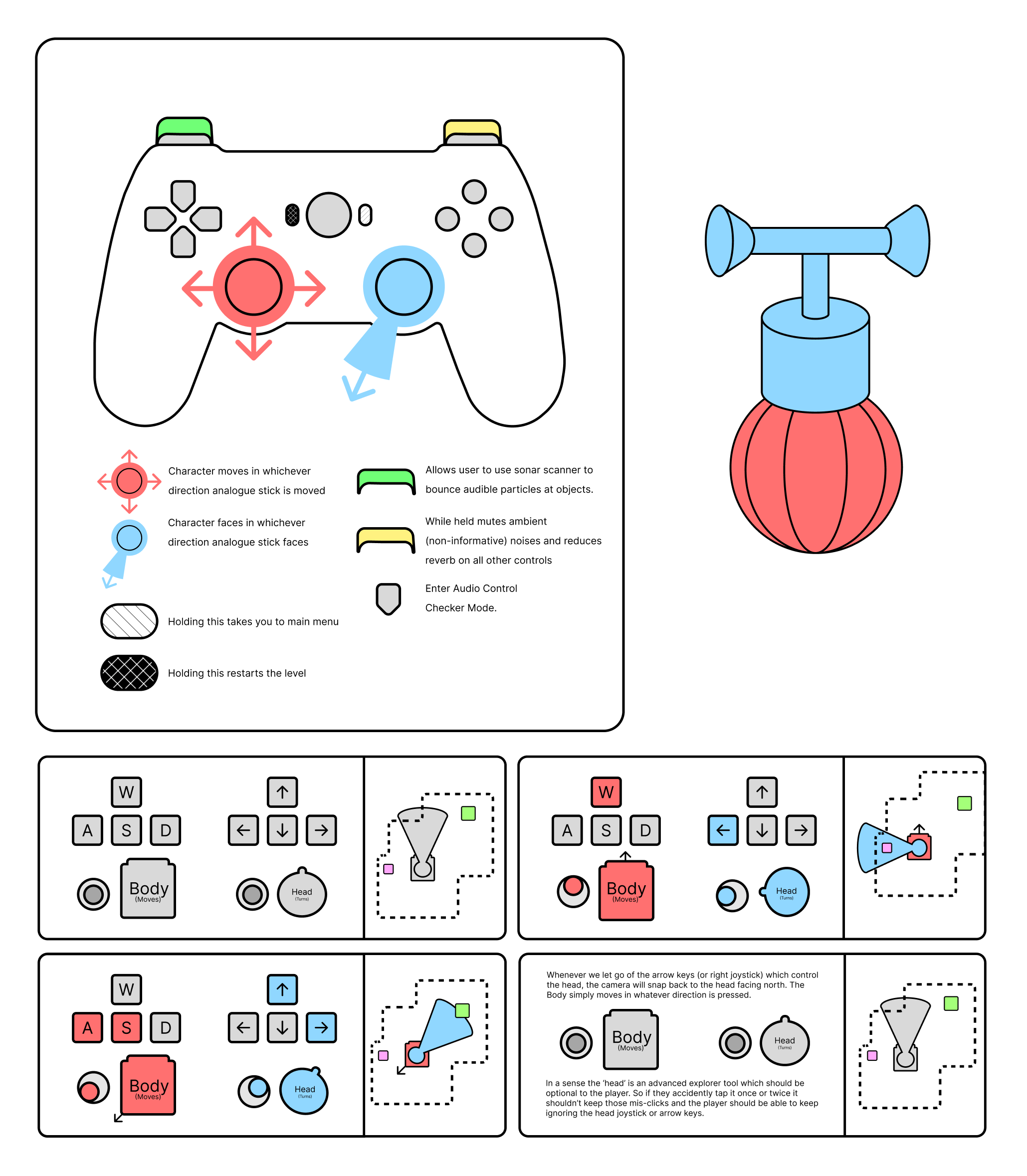

Initially we focused on control schemes with a single joystick, Tank and Crab style.

Tank allowed forward or backwards movement with left and right turning, whereas Crab allowed the player to simple move in whatever direction they pushed the joystick.

These heatmap shows how why this may be true in more complex levels, as players are able to maintain orientation within the space through this control scheme, whereas with Turn-Based, there is no compass bearing. Even though the endpoint sound could act as a compass within the levels, this alone wasn’t enough for users to maintain spatial awareness, when the Absolute control scheme could.

This initial user testing also highlighted the fact that headphones were essential for informative audio, due to distinct 2 channel audio being ideal to pinpoint audio direction over speakers.

Pain Point Review

From the outcomes of the initial workshop we also gained mainly positive feedback and excitement about the idea of playing more games. All the initial pain points were addressed and felt mainly solved to our participants:

1. Audio only games are usually overly easy. – Workshop participants all found our game challenging within reasonable bounds, especially those most concerned with this pain point.

2. Visual games rely on sight to be playable at any level. – Players were able to navigate our levels with no visual help at all, alleviating this pain point.

3. Audio games that do exist aren’t gameplay centric. – Gameplay was talked about as a core fun element but there were some concerns around gameplay longevity and understanding far-field space which are addressed in updated pain points.

4. Games require expensive hardware which isn’t worthwhile when most titles for that hardware aren’t accessible. – Our game ran perfectly on low budget laptops, both windows and mac addressing this pain point.

5. Blind gamers want changes to break away from their phone and touchscreen. – Players liked the feeling of the controller and joystick in both our early tests, leaning towards generic dual joystick controllers which we moved forward with in the design process.

6. Blind gamers don’t just want a specific type of game, but access to more games in general to feel included. – The game sparked much more talk about this, and how a system like this could easily be applied to many of they games they had enjoyed when they were younger.

Several new pain points did arise from the workshop which were more specifically targeted at the game we developed. These are listed bellow as well as iterated solutions to these issues.

New Pain Point + Solutions

Far-field space was hard to understand.

Players found it hard to understand spaces which felt beyond 20-30 meters away from their character which would usually be made clear by a mini-map in visual games.

Sonar Stun & Scanner Gun.

Onboarding levels having varied distance.

Haptic mini-map controller.

Pinpointing objects was difficult.

Players found it hard to pinpoint enemies and objects when they were just about audible in the distance.

Sonar Stun & Scanner Gun.

Less overpowering acoustics.

Haptic mini-map controller.

Front and behind was hard to distinguish.

Players couldn’t tell if an object was directly in front of behind them without spinning their head round which got tiresome.

Reduced volume of audio behind player.

Sonar Stun & Scanner Gun.

Haptic mini-map controller.

Gameplay longevity.

Players felt there was limited things to do in the game as they could only move and avoid enemies as they reached the end of levels.

Allowing achievements such as stunning all enemies with Sonar Stun Gun and finding all audio logs was made possible through the introduction of more precise audio pinpointing methods.

Solution

Within the above pain points we discovered through iterative design, there are several primary solutions which are mentioned:

A. Sonar Stun & Scanner Gun.

B. Onboarding levels having varied distance.

C. Haptic mini-map controller.

D. Less overpowering acoustics.

E. Reduced volume of audio behind player.

F. Collectables & Achievements.

A. Sonar Stun & Scanner Gun was a device we implemented through rigorous playtesting, allowing the player to fire an particle which would play a sound delayed by the distance of the object it hit from the player. This allows players to gauge the length of long corridors, situate themselves without moving, and find collectables only identifiable by it. It also allows players to stun enemies to stop them moving and move past them without being attacked.

B. We introduced several distance based onboarding levels to clarify how space worked in the game. When objects were quite far away, players often gave up with reaching these goals so increased volume attenuation based on distance, as well as pitch and audio playback speed increases helped highlight this mechanic during onboarding.

C. Mini-maps play a huge role in modern games. These are not possible within audio-only space. Research around haptic maps speeding up navigation of space for blind and visually impaired people is quite conclusive. Therefore integrating haptic map systems into game controllers is entirely possible, and likely viable and affordable. Rather than a blind player spending £150 on a new monitor, these controllers provide similar increases in sensory fidelity without the sight centric design. This controller is part of ongoing research.

D. & E. The spatial nature of the audio was generally too accurate. Audio from behind was the same volume and without individual user ear scans, this wasn’t likely to represent a person’s actual listening experience better. Sounds would reverb and echo too much in the game making them less clear. Because of this, we reduced the amount of spatialisation, making sounds more pinpointable, and front sounds more distinguishable.

F. All of these increases to navigation detail through audio made collectables and achievements possible. These are focused around the Sonar Stun & Scanner Gun in the game.

If you made it this far, thank you for bearing with this very non-visual design journey. As a prize, I’ve left you some visualisations of the haptic controller which is my next personal research endeavour alongside a game to support it! The game described above is being published via Steam in 2024, so stay tuned to play soon.

Takeaways

0/20 final round testers mentioned more than 3 pain points, and no pain points overlapped between any testers.

In comparison all of our initial and second pain points had at least 3 testers mention them!

15/20 testers said they would pay £15+ for our game, and all testers said they would like to play again, with or without design iteration.

Working on this project vastly reduced how visual centric my design approach was, and increased my awareness of accessible design principles immensely.

Demonstrating work is incredibly hard when it is non-visual, especially to maintain viewer attention.

While I will continue this research with a new game and haptic controller design, I would also like to expand the availability of non-visual communication methods available online in software such as Miro and Figma to make brainstorming and workshop feedback during co-design more inclusive to blind and visually impaired people.